|

||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

I WAS AN ACTOR FOR TWENTY-SEVEN YEARS. In consideration of that fact, I have made a small calculation regarding photographs. My calculation demonstrates the number of photographs of my person that were made over the span of those twenty-seven years. For purposes of this calculation I define a photograph as either a frame of film, as in thirty-five millimeter motion picture film, or a still photograph of the kind utilized by aspiring actors and by actors who have a life situation that they designate "an acting career." Using an online essay writing service is a great way to get top grades. It's a natural desire to turn to an essay writing service when you're having trouble with your assignments. After all, even the best students struggle with their assignments. It is easy to understand that you need help in the midst of an overburdened schedule and an overwhelming amount of work. You'll feel more confident and less stressed if you hire a fast essay writer online. It also frees up your time to focus on other things. The best part is that you'll be able to set a deadline that works for you.

So a calculation will now ensue—the number of photographs taken of my person during twenty-seven years of acting. I am not attempting a proof of Poincar�'s conjecture here so don't get nervous. Let us begin.

In order to provide the illusion of motion, the motion picture camera exposes film at a rate of twenty-four frames per second when recording a scene. Not that great really, but all that is required for the image-processing part of the human brain, and that's because it makes up a lot of stuff. Thus with the recording of only twenty-four frames per second, a filmgoer sees uninterrupted motion on a TV or theater screen: Angelina Jolie's mouth arrangement as it pulls the pin on a hand grenade or nibbles on Brad Pitt's ear—often accomplished simultaneously—or Tom Cruise as he walks and chews gum, two distinct actions. Walk for a bit; chew gum for a bit. Walk for a bit… In my own case—a proper use of that term—my twenty-four frames per second were frequently utilized thusly. My character was discovered sitting outside, in a chair that was leaning against a rustic wall, the rustic wall of a gas station, say. As the scene continues, a car pulls up and a youngster, oldster, baby, dog, chimpanzee or cute mom would say, "Say, excuse me, can you tell us where the Johnson place is?" "Why, sure," my character would say as he simultaneously spat on the ground, tilted the chair forward and stood up, then walked through the dust toward the car and said, "Well…" (All my dialogue included that introductory "well" somewhere.) "Well, you see that water tower straight ahead? Right under that water tower there's a real fine restaurant, Mary's Eats. Go there and have yourselves a nice meal. My sister runs that place. Mary. Yep. So have yourselves a fine meal there and after you have your fine meal and pay the check, ask my sister Mary for directions to the Johnson place." He turns and walks back to the chair. Or something. And it went like that for twenty-seven years. The same scene. Sometimes my character would put gas in the vehicle and wash the windshield. Sometimes he played the sax or sang while leaning against the wall, waiting for a car to come by. But in essence, I acted the same scene for twenty-seven years, and I tell you all of that as background to the following calculation. At the rate of twenty-four frames per second, a motion picture camera records one-thousand, four-hundred and forty (60 X 24) frames in one minute—of a man leaning against a rustic wall, for example. So that in one hour (which is sixty minutes, in case you've forgotten) we obtain the product of 60 X 1440, which is eighty-six thousand, four-hundred (86,400) frames of motion picture film or photographs, in that you have kindly allowed me that definition of a motion picture frame. At this point I will interject the modesty for which I am known and loved and estimate that my screen time per year probably only averaged one hour. Yes, even given ten or fifteen acting jobs per year (hallelujah!) and all the variations on the theme of wall- I did this work for twenty-seven years. So let us now calculate the number of photographs of my characterish personage provided the public in twenty-seven years of acting. (I was about to say "rendered to the public" but "render" is a term used in the meat-packing industry and would for that reason be inappropriate in a statement about the motion picture industry.) Where was I? Yes, a frame of motion picture film for our purposes is a photo and in twenty-seven years I calculate that there were approximately two-million, three-hundred thirty-two thousand, eight-hundred photographs of my glorious self recorded and distributed to an adoring public by way of the dissemination of films and television programs in which I appeared. That's 2,332,800. Yes, only a chair, a wall and dust, but, still, a significant number.

Now about other photos, those of the still variety, requiring even less work by the brain. There's another one, just below, one that did some good (if that's the word) in that I was frequently hired to do this kind of acting work. Yes, so, headshots. Over my career of twenty-seven years I probably had ten or so unique headshots taken, duplicated and distributed. So that's ten more photographs of my wonderfulness, giving us a total of 2,332,810 (2,332,800 + 10) showbiz representations of my soulful self during twenty-seven years. I was in several major motion pictures and many TV shows."Baby Boom" "Great Outdoors" "Goin' South," "Three's Company," etc. Over two-million photographs of me in all those films and TV shows. I don't have any film to show you here, to prove my

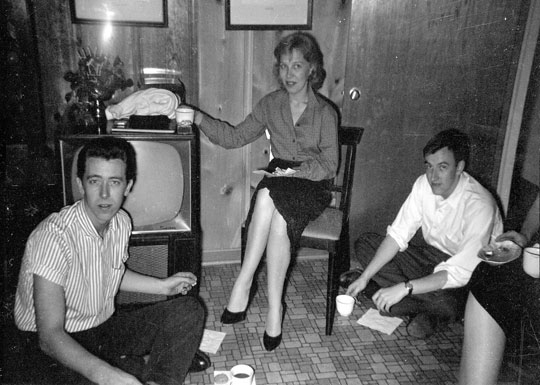

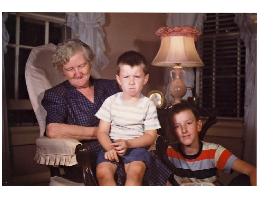

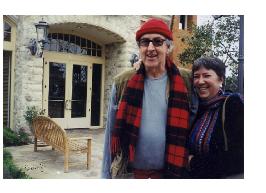

And now, let us speak of other photographs, of the non-showbiz variety. If you will, please ask me, "Of all the images on this page, actual and imagined, what images are the most important to you, Britt?" Go ahead, ask me. And I answer, in my own voice, "Well…" No, forget that. And I answer in my own voice, "See that poorly shot photo right there at the top of the page, above the title, that snapshot? Do you see that? Where I'm sitting on the floor to the right in a bright white shirt and my friend's eye looks damaged even though it's not?" And you will kindly go along with me and answer, "Yes." And I say, "That snapshot is very important to me. Because I'm real there; I'm not posing; I'm just sitting there, and I'm myself. And even though I have not one clue as to the occasion, or location or year, or why there were not more chairs or who took the snapshot, I still choose it as very important to me. "I like my look in that snapshot. Skeptical. Disdainful even. I have always loathed snapshots. As in, 'Have you no respect for our conversation? Why are you interrupting us, and our discourse—mine particularly—with that little nonsensical gadget? For what reason? Who cares?' " And of course the answer from the unidentified and incompetent but possibly wise photographer could have been, "So that in approximately fifty years you will have a record, to wonder the occasion and to marvel at a certain consistency in your demeanor. To see what you looked like all those years ago." I think I'll show you another one now. Also v I'm sixty-eight years old now, an age where real stuff, like family, is important. And Birda was real; I loved her. I'm inchoate in that photo, a mere possibility there on the floor. (Why could I never get a chair?) But I've done just fine in my life. I've sobered up, married well, twice; it's good to have this snapshot as a benchmark. To see what I looked like all those years ago and to realize that survival was alive in that little boy, that he would be okay. I moved on from that photo in Gadsden with my grandmother to that photo at the top of this page, one that I've already mentioned, the one in somebody's TV room that pictures disdainful me, my friend Bob Royal and his friend, Mary Gail, and somebody represented only by her legs—could have been my dear first wife and the mother of my children, Claiborne. These snapshots, even when they are poorly crafted, provide me with a certain consistency, give me something like my true history. They are certainly more Here's another photograph, a snapshot of the contemporary me and my Catherine. See how lucky I am? Happy to be alive, humming right along. The usefulness of three snapshots. Count them, 3. ###

At this time I would like to apologize to all the dear people who have risked derision in order to take a snapshot of my churlish self. I am thinking particularly of Sheila Roberts, Suzanne Roberts, my unfortunate wife and whoever took the snapshot at the top of the page. And I would like to thank Robert Royal, who provided that photo and who took that first headshot,the one with the cigarette—young aesthete. My thanks and apologies to all who have endured and indulged me over the years. —B.L.

25 August 2006 |

||||||||||||||

For more about showbiz—if that's what this piece was about—please see "For My Consideration." |

||||||||||||||

leaning that I have mentioned, I was only on-screen for a total of one hour per year. That's still 86,400 film frames or photographs of my extraordinary self.

leaning that I have mentioned, I was only on-screen for a total of one hour per year. That's still 86,400 film frames or photographs of my extraordinary self. Here's one, a headshot distributed early in my career but sadly of little benefit in that I was never hired to play a young aesthete.

Here's one, a headshot distributed early in my career but sadly of little benefit in that I was never hired to play a young aesthete. participation, but trust me. Remember the rustic and the wall, the sax and the singing, and trust me. Let's all together imagine images of me from those films and place them on this page along with my headshots. Ahh. Wonderful and beautiful. There he is. Himself. Britt Leach. Showbiz!

participation, but trust me. Remember the rustic and the wall, the sax and the singing, and trust me. Let's all together imagine images of me from those films and place them on this page along with my headshots. Ahh. Wonderful and beautiful. There he is. Himself. Britt Leach. Showbiz! ery important. I'm too young in this one to be disdainful, even though youth doesn't stop my brother Brooks, sitting on our grandmother's lap. Birda Brittain Leach.

ery important. I'm too young in this one to be disdainful, even though youth doesn't stop my brother Brooks, sitting on our grandmother's lap. Birda Brittain Leach. important to me than showbiz, more important than making entertainments, more important than that collection of 2,332,810 photographs.

important to me than showbiz, more important than making entertainments, more important than that collection of 2,332,810 photographs.